✍🏼 Why is community in decline?

Our quality of life is better than ever, yet we're more disconnected than ever. It's time to bring connection back

My people! Hello.

Happy Sunday to the 19 of us. I’m so glad you’re here.

As is likely obvious at this point, I’m obsessed with connection, and I wanted to wrangle some thoughts on why it is that connection and community have been in decline as modernity marches on and our quality of life gets ever-better.

Here, I try to do that.

I also wanted to call out that at the bottom, I’m throwing some of the most interesting and exciting things I’ve devoured recently, so if my thoughts droning on bores you to tears, at least scroll to the bottom to check out some of those links before you ✌🏼 out.

Hope you enjoy, and if if you do, I’d be grateful if you shared this with a few people you think would also enjoy it.

20 is a good start, but let’s see where we can go with it.

Cheers,

Devin

Why is community in decline?

I’m not going to bury the lead: we’re more disconnected than ever.

We’re disconnected from each other and our communities. We’re disconnected from ourselves - our values and identities, our wants and needs, our emotions and our bodies.

It’s my belief that this point - that we’re increasingly disconnected, that community has been in decline over the recent decades - is generally accepted. It’s squarely in our generation’s zeitgeist.

If you don’t agree, I’m not going to take the time here to try to convince you - I’ll save that for another time. Plus, there’s much discourse on this topic in news coverage, podcast interviews, and (other) essays all over with the hard statistics that I’d simply be regurgitating here. I’ll spare you for now.

The point that matters is that losing our sense of connection and our communities is bad. It leaves us lonely and suffering.

As I’ve said elsewhere, I believe we need more connection in our lives - and my work is to bring it back.

As a first step: it helps to understand why something so crucial is in decline.

So, let’s explore why this is the case.

Our systems help us survive

By and large, systems that exist in our society today do so for good reason.

One way to think about the systems that we have in place today (e.g., capitalism, democracy, etc.) is through the lens of evolution. Evolution drives everything.

With this in mind, we can, by and large, come to the conclusion that the systems underpinning our society, particularly the ones that affect a lot of people, or have been around for a long time, came to exist, and then persist, because they help increase our chances of survival.

Let’s take capitalism - a system that, at its core, exists to protect individual economic freedoms.

To focus the discussion solely on the principle of individual economic freedoms, however, would miss the point.

What matters is the downstream outcome of those economic freedoms - individual pursuit of profit motive driving efficient resource allocation towards uncertain projects of potential future value, driving innovation and novel technology resulting in collective economic and societal prosperity.

Collective economic and societal prosperity is the point.

Those that believe in the merits of capitalism believe that our lives (and at a more basic level, our chances of survival) improve as a result.

New doesn’t necessarily mean better

The problem is that not all systems are good.

There are plenty of examples of failed economic or social experiments put in to practice by those that believed their new system would better achieve our end goal - improved odds of survival and a better life.

Another lens that’s relevant here is that of the Lindy effect - the heuristic that suggests that the longer something has existed, the longer it is expected to continue to exist in the future.

With our Lindy hats on, we can assume that of our systems, the older ones are more likely to have greater underlying value with respect to our existence than the newer ones.

The world is also incredibly complex.

In the current state of our ever-evolving American experience, capitalism is only one of countless other systems that, to varying degrees, in ways both seen and unseen, shape the way the world works, and our experience within it.

It’s impossible to clearly map the countless systems, the second- and third-order (and beyond) impacts of these systems on each other, and the ways that the various systems in the world shape our lives and society at large. Humans have been trying to do this for millennia, and I’m not sure we’ll ever stop.1

All this is to say that especially for the new(ish) systems at play in our world, it’s important to look at, in addition to the ways they drive a better world, the challenges they bring.

As anything advances and becomes ever-pervasive, certain things get left behind. In a world of trade-offs, as we choose the systems that we want governing our world, we must emphasize certain things that necessarily come at the expense of others.

We can’t have it all.

The costs of our western culture

We kicked off by highlighting one such cost of the systems at play in our western world - the decline of community, and a dramatic and ever-increasing sense of disconnection.

But back to the key question - why is this?

One of the greatest strengths of our western culture is also (as is so often the case) one of our greatest weaknesses.

The very things that have brought us into what is objectively the best time in human history to be alive2 have led to optimizing for things that leave our humanity behind

We optimize for ambition, achievement, money, efficiency, optimization, novelty, science, technology, status, popularity.

Connection, vulnerability, emotion, presence, authenticity are non-optimal on our modern scorecards, and our humanity gets left behind as a result.

We’re good at surviving, and forgot how to thrive

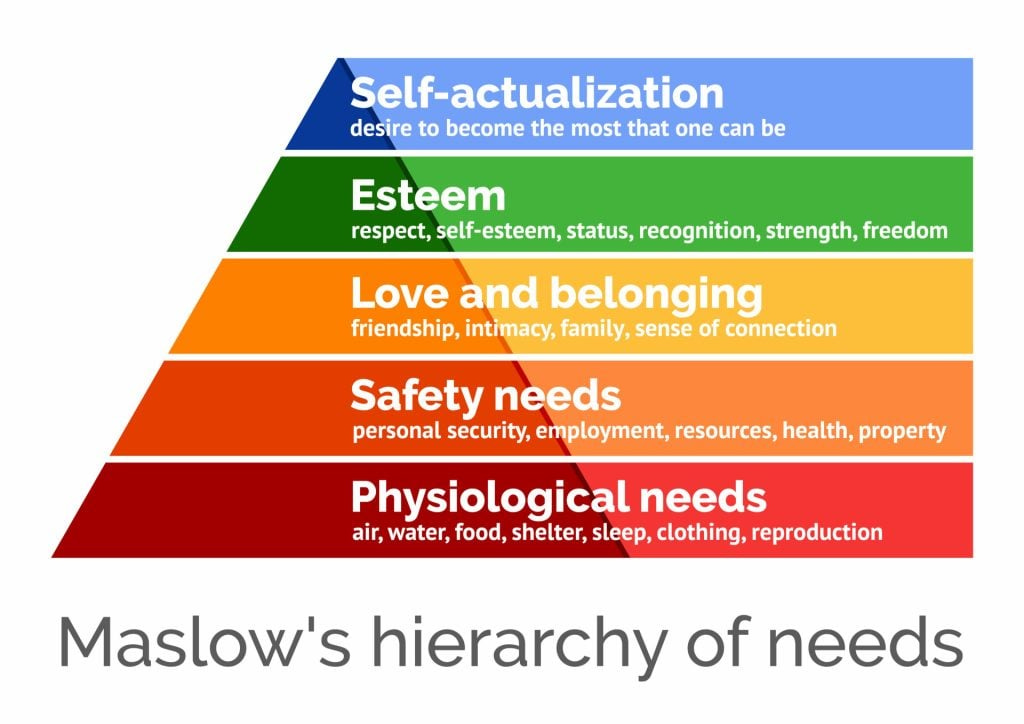

Not that survival is always simple, but we humans do have more needs than simply staying alive - love and belonging, esteem, and self-actualization to be exact.

I call these our connection needs, and they include both connection to others (love and belonging), as well as connection to ourselves (esteem and self-actualization).

Once we’re beyond fighting for our lives, meeting our connection needs is what brings us into a state of more comprehensive well-being.

Clearly, none of our connection needs matter if we can’t prevail in our fight for survival.

For the vast majority of our existence, physiological and safety needs were all we had time and energy for in our struggle for continued existence in this chaotic destructive backdrop of unyielding entropy that rules this floating space rock we call Earth.

But wow are we lucky today.

The beauty of being alive in a time where our physiological and safety needs are met better than ever is that we have the freedom to pursue lives that better fulfill our connection needs in pursuit of an existence of greater happiness and well-being.

To make a bold claim - while we haven’t defeated death (yet), we’ll keep trying. But along the way, we have some ~80 years of life to live where working to meet our connection needs towards the top of Maslow’s hierarchy is what matters.

This is where we struggle.

Our struggle is a uniquely modern phenomenon.

While today we have incredible freedom with respect to how we use our time relative to our ancestors,3 we’ve actually been evolutionarily shaped over the several hundred thousand years of our existence to need, for a sense of connection and well-being, elements of how our species used to spend the majority of its time.

It’s interesting to think about the hierarchy of needs in the context of an evolutionary lens.4 The ways our ancestors used to have to spend their time to meet needs at the bottom of Maslow’s hierarchy in the fight for survival spawned our connection needs of emotional, social, and spiritual well-being at the top of the hierarchy.

We often hear that humans are a social species relative to the rest of the animal planet. Why is that?

What I’m saying is that it’s not simply because we enjoy each others’ company.

It’s because the way that humans were able to better meet our survival needs was through collaboration with other humans. Our connection needs are intertwined with our survival needs - and came about because of them.

Our need for love and belonging came out of the reality that the ways we met those needs bettered our chances of meeting the more fundamental, base survival needs. Forming collaborative, high-trust communities of multiple enabled a more efficient and effective force for survival than a single person.

We can say the same thing about the layers above love and belonging on Maslow’s hierarchy as well. One way to understand esteem and self-actualization is that in a very Darwinian way, they increase our value in our communities, and therefore our odds of survival. The higher value an individual is, the more secure their position in the community and its supply of survival resources.

There’s an elegance to all of this.

One such way is that we’ve adapted to thrive by doing precisely the things we needed to survive for the bulk of our existence. This means that, since we needed to do these things to survive, the ways we spent our time not only contributed to our survival, but also our more transcendent goal of connection and well-being.

There’s a beauty to this alignment and simplicity.

To bring it all back to connection and community: we’re wired to need them, and the way we as a species used to spend our days surviving also provided us with connection and community.

The externalities of modernity

We often think of technology incorrectly.

In our modern world, we think of technology as computers, space ships, and flying cars.

What technology really is, from the perspective of first principles, is “the application of knowledge to solve problems or meet needs.”

From this perspective, everything we’ve done that makes us better at survival is a technology - even things like verbal, spoken language, societal rules of law, and man-made fire.

Technology is why we’re the superior species on this planet. Technology runs (and has always run) our world. Technology rocks.

One of the (quite ironic) paradoxes of our species is that as a result of being so good at technological innovation, and therefore survival, we’ve freed up vast amounts of our time to spend in much more “enjoyable” ways that require much less “work” than in the past.

So today, we spend our time quite differently than our ancestors.

While we’re better able than ever to meet our survival needs due to technology, technology has been optimized and utilized to meet survival needs, not needs of connection and community.

The problem is that our needs evolve much slower than the rate of our technological innovation.

Although we still have the same connection needs, the ways we spend our time have changed. The technology that enables these new ways of living has left a connection and community gap that our ancestors never had to worry about filling

We’re better able than ever to meet our survival needs, and our connection and community needs are more unmet than ever.

Survival (objective and simple) vs. connection (subjective and complex)

Another challenge we face with respect to the nature of survival vs. connection needs is that our survival needs are much more objective and simple, and connection, more subjective and complex.

Survival is pretty clear. Alive or dead. Hungry or satiated. Thirsty or hydrated. Objective.

Connection is much more squishy. More complex. More nuanced. More intuitive. Subjective.

Hundreds of millions of Americans can comprehend, relate to, and pursue the American Dream - a home, a yard, a fence, a dog, a spouse, 2.5 kids.

Billions around the world can open their phone and see a scorecard for success and worth in the form of a bank balance.

But when it comes to the deeper emotional connection and human pursuits of the soul, we are the only being in the world who has our specific set of values, experiences, and circumstances - and the only one who can truly know to what degree our deeper human needs of connection are being met.

And even then, it’s nuanced. You can’t put a finish line on connection and well-being like you can on other goals more survival-oriented in nature, like capacity to afford the price tag of a 3-bedroom penthouse in Manhattan.

As they say, “what gets measured gets managed.” And what can get measured will get managed.

But maybe more relevant here is something like what can’t get measured won’t get managed.

When it’s objective and measurable, it’s simpler. Humans love simplicity, so we fixate on those things.

But simple doesn’t always mean most important.

When we focus on our simple needs and wants, we can lose focus on the important, more complex needs (e.g., connection, fulfillment, etc.). As many of us know all too well, we can meet many external standards of success and still feel incomplete and empty on the inside.

This is the source of so much of our unhappiness, loneliness, and suffering in our modern world.

The slippery, nuanced complexity of our higher connection needs also makes them really challenging to describe and discuss.

This was supposed to be a short piece, but each time I come at the topic, I feel like I can’t quite nail it. To cover the nuanced contours of the ideas behind our deeper humanity, it takes different approaches from different angles.

It can feel like a Zen koan, frustratingly so at times. In many ways, it’s the opposite of the objective nature of our survival needs, and the technologies we invent in their pursuit.

Maybe even more relevant: if being unable to measure something makes it challenging to manage, being unable to describe it makes its management even more daunting.

So, at the same time that we’ve been enjoying the benefits of our ancestors’ technological innovation, further cementing our species’ life on this planet and freeing up our time for more varied and pleasurable uses of our time, we’ve not only gotten away from spending our time doing the things that satisfy our deeply human connection needs, but also are using all this freed up time and energy to doggedly pursue the objective, measurable, simple pursuits of our modern technological society at the expense of the subjective, complex, nuanced pursuits of a more connected, fulfilling, and rich human experience.

That was a mouthful, but let me put it simply - the same needs with less time and effort meeting them = dis-ease.

It’s time to bring connection back

I have an optimistic view on all this.

I don’t believe that challenges mean we burn it all down.

Just because technology has advanced and cost us deeper levels of connection doesn’t necessarily mean we should forsake it all and go live in the woods like the ancients.5

I’ll say it again - technology rocks.

Air conditioning is a godsend. Airplanes are a miracle.

Let’s keep innovating and making life better.

I’ll also say this - we’re more disconnected than ever, and we’re hurting for it.

It’s time to bring connection back.

The cool thing about this all is that we don’t even need to believe we should do this as charity for somebody else. Let’s do it for ourselves first.

Every animal fights for survival. What makes us human is the capacity for deeper and richer pursuits of connection and meaning.

Maybe (definitely?) I’m a romantic, an optimist, an idealist, but in my view these are the noblest of pursuits. Let’s pursue them.

The good news is that, though we may be straying, we are wired for connection. We do know how to do it.

It’s quite simple. Challenging, but simple.

It takes effort. Risk. Vulnerability.

But it gives us back more than we can imagine.

Our humanity.

It’s what the world needs now more than ever. But it’s possible.

This is my project.

This is The Comma Project.

If you enjoyed this newsletter, forward it to a curious friend and tell them which idea they'd love.

Click here to read the archive.

Click here to follow on Twitter.

If you were forwarded this email, click the button below ⬇️ and enter your email to subscribe.

Curiosities

David Whyte on life’s work

Paul Graham on how to do great work, with some key points as a TLDR. Very long piece, but very worth the read. Curiosity and consistency are two key themes in Paul Graham’s writing. Some favorite quotes:

“There's a kind of excited curiosity that's both the engine and the rudder of great work. It will not only drive you, but if you let it have its way, will also show you what to work on. What are you excessively curious about — curious to a degree that would bore most other people? That's what you're looking for.”

“If you're interested, you're not astray.”

“Curiosity is the key to all four steps in doing great work: it will choose the field for you, get you to the frontier, cause you to notice the gaps in it, and drive you to explore them. The whole process is a kind of dance with curiosity.”

“The reason we're surprised is that we underestimate the cumulative effect of work. Writing a page a day doesn't sound like much, but if you do it every day you'll write a book a year. That's the key: consistency. People who do great things don't get a lot done every day. They get something done, rather than nothing.”

“To see new ideas, you need an exceptionally sharp eye for the truth. You're trying to see more truth than others have seen so far.”

“Talking or writing about the things you're interested in is a good way to generate new ideas. When you try to put ideas into words, a missing idea creates a sort of vacuum that draws it out of you. Indeed, there's a kind of thinking that can only be done by writing.”

Another Paul Graham piece on how to do what you love, with some favorite quotes:

“That's what leads people to try to write novels, for example. They like reading novels. They notice that people who write them win Nobel prizes. What could be more wonderful, they think, than to be a novelist? But liking the idea of being a novelist is not enough; you have to like the actual work of novel-writing if you're going to be good at it; you have to like making up elaborate lies.”

“It's hard to find work you love; it must be, if so few do. So don't underestimate this task. And don't feel bad if you haven't succeeded yet. In fact, if you admit to yourself that you're discontented, you're a step ahead of most people, who are still in denial. If you're surrounded by colleagues who claim to enjoy work that you find contemptible, odds are they're lying to themselves. Not necessarily, but probably.”

“Another test you can use is: always produce. For example, if you have a day job you don't take seriously because you plan to be a novelist, are you producing? Are you writing pages of fiction, however bad? As long as you're producing, you'll know you're not merely using the hazy vision of the grand novel you plan to write one day as an opiate. The view of it will be obstructed by the all too palpably flawed one you're actually writing.”

“Whichever route you take, expect a struggle. Finding work you love is very difficult. Most people fail. Even if you succeed, it's rare to be free to work on what you want till your thirties or forties. But if you have the destination in sight you'll be more likely to arrive at it. If you know you can love work, you're in the home stretch, and if you know what work you love, you're practically there.”

This is why we need collective dialogue with more nuance than we have today, but I’ll also hold that topic for a different discussion.

Yes, I know this may seem like a weird statement in a piece that is lamenting the decline in one of our most crucial components of human well-being.

To untangle this confusion - we are at the best moment of any time in human history with respect to objective measures of well-being (death in childbirth, poverty levels, literacy rates, etc.). It is possible to acknowledge both the fact that we’re in the greatest moment in human history and address our challenges and work to improve them. In fact, I’d argue this is the way we should be.

Another way to frame this would be to genuinely ask yourself what year you’d choose if you had to be dropped into any society, in any city, in any body of any skin color and economic background completely at random. You’d say today. (If you think you’d say no, this is one point that I’d argue with you over.)

In that, on average, we require drastically less time in our day committed to meeting our basic survival needs.

You’re probably sensing a theme here.

Though if that’s your jam, don’t let me stop you.

i don't know what the blog version of a standing ovation is but I would have stood on my feet for a full 5 minutes